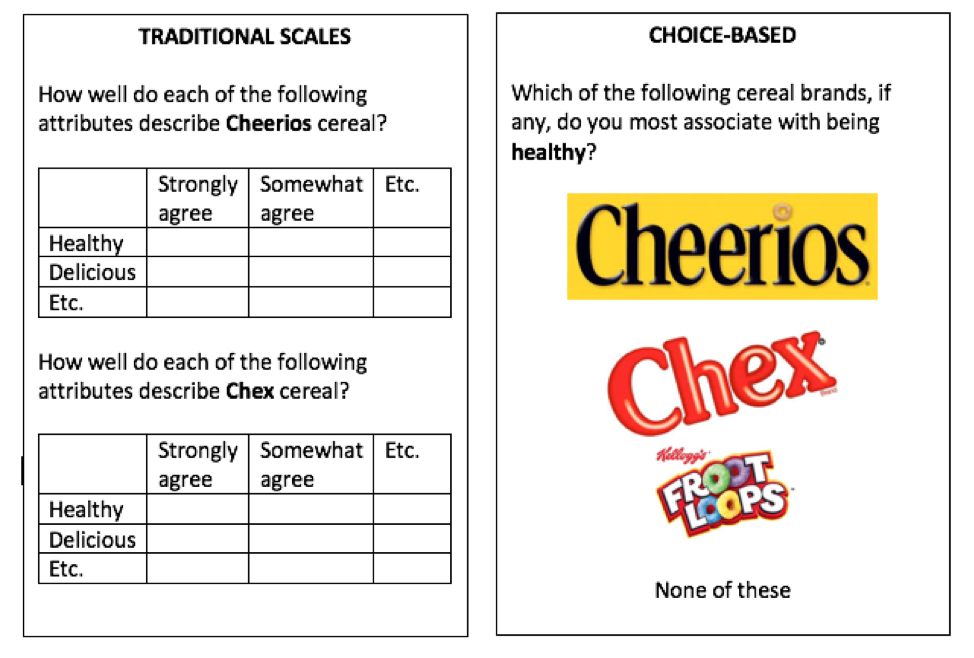

An overriding theme in market research innovation is getting closer to the way people actually think, feel, and behave. We’re seeing more techniques and approaches that allow us to observe and measure versus ask. The body of evidence for this shift is extremely compelling, especially when combined with the latest cognitive and behavioral science advances. One way to do this within a quantitative research context, is to focus on respondent choice as a measure, versus traditional scale-based responses. At a recent market research industry conference, Dave Santee of True North Market Insights gave three compelling arguments against traditional Likert scales, saying: they are not comparative or in context, respondents dislike them and don’t make decisions that way, and different groups/cultures use scales differently. Multiple expert sources agree that research approaches that ask respondents to make a selection from a relevant choice set are more predictive than research designs that ask respondents to rate or score those same options on a scale. We know that our brains love shortcuts—we operate in deselection mode when shopping, not rating each and every product before arriving at a decision. By the way, this approach also gets around the dreaded matrix question! Here is a simple example that works within a traditional survey framework (truncated just to make the point): There are trade-offs. If you’re used to getting a rating for every attribute for every brand, that won’t happen in this type of research design. But if the findings more accurately reflect the way that people feel and act, that seems like a good trade-off to make. The benefits will go to those who can convince their organization to throw away the old scorecards, dashboards, and databases. As an ex-corporate researcher, I understand that’s no easy feat!

In addition to restructuring questions for choice (versus scales) within a traditional survey framework, there are other, entirely choice-centric research methodologies, including MaxDiff, Conjoint, Prediction Markets, and Virtual Shelf/Store research. These rely exclusively on respondent choice for data collection (but can also be supplemented by direct questions within the broader study). Virtual shelf tests are something I’ve personally been doing a lot more of recently. They are my preferred way of doing packaging testing, but I’ve also used them for planogram/shelf set design and even new product qualification (in lieu of a traditional concept test). Instead of asking purchase intent or other scale-response questions, respondents simply shop for their desired product(s) from a category shelf set, generating product/package selection and spending metrics. This type of testing doesn’t have to be restricted to “shelves” if that’s not relevant for your category or brand. The key principle is to put the product (or service) in the context that consumers will actually evaluate and make the purchase decision. Other examples might include: mocked-up Amazon.com pages of products, restaurant menus, or website lists of services (don’t forget to include prices!). - I have very classical CPG market research background, so I cut my teeth on survey scales and grids and live for the thrill of a top quintile purchase intent score, but I also love learning about new methodologies and techniques that get us closer to predicting actual consumer behavior in a complex reality. Choice-based research techniques can not only help us better reflect and predict reality, but they also have the benefits of being more engaging for respondents and more mobile-friendly, both of which lead to higher survey completion rates, more representative sample, and ultimately, better quality and more accurate data.

1 Comment

I recently attended the inaugural West Coast Quirk’s Event in Irvine, California, a market research industry conference focused on “big ideas, real-world solutions”. Looking back, the unofficial theme of the presentations I saw seemed to be: let’s get closer! This played out in multiple ways: get closer to reality with new ways of collecting data, including in-the-moment research, get closer to consumers/customers with co-creation and empathy in research, and finally, get closer to seeing the whole picture with mixed methods and data integration. Here are a few more specifics and examples from the conference to bring these themes to life. In-the-moment research ensures authenticity in data collection

Co-creation and shared experiences compress timelines and foster empathy

Mixed methods and data integration provide holistic insights

We’ve probably all seen examples of awful questionnaires or discussion guides. If you want more, there are plenty online—check out @MRXshame on Twitter for some hilarious ones. The crux of the issue is that we, as market researchers—client or supply side—have all been guilty of designing surveys that we would never want to complete ourselves. We conveniently forget or ignore how tedious those grid questions are, how annoying it is to answer the same question worded slightly differently multiple times, how impossible it is to remember something you bought six months ago, and how your attention span starts to wane after 10 or 15 minutes. There are significant consequences of bad questionnaire writing, in the form of bad data and unreliable results—from straight-lining or random responses from the people who do finish your survey to chronically under-representing certain groups from people who drop out. For example, Quirk’s published a compelling study in February 2016 (“The impact of survey duration on completion rates among Millennial respondents”) which found that there’s a major drop-out inflection point among Millennial respondents after 15 minutes. Education and training are critical to master good research design and quality, but even if we have a good foundation, we can still lose touch with the people who respond to and participate in our research. To that end, I want to offer a few simple suggestions that we can all start applying today to help us create research we would actually want to participate in ourselves. 1. Be someone else’s respondent. Sign up for some online quantitative research panels or apps (e.g. e-Rewards, Field Agent, SurveyMini, The Pryz Manor, etc.) as a respondent. Always be honest—if they’re screening out market researchers, you can’t participate. But for the ones you can complete, you’ll get great ideas for what works, what to avoid, and how to make survey research more engaging. Nothing builds respondent empathy faster than taking a poorly-designed survey! I would not recommend signing up for qualitative panels though. They should all have industry screen-outs and even if they don’t, the chance of messing up someone’s research in a qualitative setting with small base sizes is just too high. 2. Eat your own cooking. Take your own survey. No, you might not be the target consumer, but you are a human. If filling out that complex matrix question drives you nuts—and you wrote it!—imagine how someone who doesn’t care nearly as much about your category/business will feel. Look with alien eyes at that creative exercise you planned. Are the instructions clear? If you didn’t know what you know about your product/brand/category, would it make sense to you? How long will it really take to find all those images or complete that storytelling exercise? 3. Phone a friend. Request peer-reviews of your questionnaires and discussion guides. If you’re on the client side, exchange surveys with colleagues for feedback, especially those outside your business unit/category if possible. On the supply side, you can also get feedback from co-workers, but just be mindful of confidentiality if you go outside the client team (i.e. use an in-market ad or package instead of the test one as stimuli, remove any proprietary client questions, etc.) If you’re an independent consultant or don’t have ready access to colleagues for any other reason, strike a deal with a few trusted professional contacts to do a “feedback exchange” for questionnaires, guides, etc. where you review each other’s’ materials on a regular basis. The confidentiality caution applies here too. 4. Straight from the horse’s mouth. There’s probably no better way to understand the real survey-taking experience than pre-testing it with consumers (i.e. not professional researchers.) There’s a range of ways to approach this—from very quick and informal all the way to an additional phase of research, depending on existing knowledge, business risk, and budget. The most informal way to do this is to find people who fit the most basic criteria (e.g. pet-owners, restaurant-goers, detergent-buyers, vacation-planners, etc.) in your workplace or among friends and family and go through your screener, questionnaire or discussion guide with them. In this context, I think it’s most effective to administer it like a face to face interview where you read the questions out loud and mark their answers. You’ll get some instant feedback as you go (e.g. facial expressions, questions about the questions, etc.) and you can also ask for direct feedback too. On the other end of the spectrum, if you’re planning a large-scale research project (multiple legs or geographies, a very high investment, or large potential business impact), doing a small qualitative phase up front to develop the questionnaire or guide can pay huge dividends. This also applies if you’re going to be researching a category/industry that’s relatively new to you and you don’t necessarily know all the right consumer language, response options, category attributes, etc. -- Whether you’re learning to think like a respondent by actually being one, or getting feedback from a professional researcher or lay-person, we can all use these insights to make our research better—a little clearer, less complex, more engaging, and ultimately, higher quality. |

AuthorSarah Faulkner, Owner Faulkner Insights Archives

July 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed